আয়, আয়, আয়রে আয়, আয়রে আয়, আয়রে আয়,

আয়রে বোঝাই হাঁড়ি হাঁড়ি মন্ডা-মিঠাই কাঁড়ি কাঁড়ি আয়,

মিহিদানা পুলিপিঠে জিভেগজা মিঠে মিঠে

আছে যত সেরা মিষ্টি আছে যত

এলো বৃষ্টি, এলো বৃষ্টি, এলো বৃষ্টি,ওরে!

Pujo is over. It is that sad, desolate time of year when, teary-eyed, we bid goodbye to Maa Durga and all the lights and festivities that came with here. Family members meet, the young touch the feet of the elderly, the men embrace each other, while the women engage in sindoor khela, a final colourful flourish before everything dies down. And no Bijoya is complete without mishti. Any discussion on Bengali sweets is bound to be incomplete, but I gave it a shot a couple of years back. The strategy? To divide sweets into three, rather arbitrary categories: those based on milk, chhana, and flour respectively. Here’s a quick recap, a whirlwind tour through the world of mishti.

Milk-based sweets echo a lot of North Indian varieties, probably even inspired by them, like rabri, payesh and kalakand. Slightly more unique are the sweets made from malai or sar, like the iconic sarbhajas and sarpuriyas. But Bengal’s USP is the category of sweets made with chhana, both sandesh, made by cooking chhana and sugar, and the iconic rosogolla with all its derivatives, all of which start by cooking balls of chana in hot sugar syrup. Dunk these into hot oil on the other hand, and you get echoes from the North, via the pantua family. Dunk in other flours and you get sweets like mihidana and laddoo. And speaking of shaped sweets, how can we forget the naru, made with both sesame and coconut, and the humble mowa, essentially puffed rice held together with sugar.

Flour-based sweets provide echoes of the Western world. There are concoctions based on pastry, notably the khaja and lobongo lotika. Unlike Western pastries, where the trio of flour, fat and sugar are combined and baked, Bengalis make a flour dough and dunk it in fat followed by a soak in sugar syrup. The batter-based jilipis and malpua find their kin in the funnel cakes and pancakes of the West, although few Western desserts can match us in saccharine strength. Batters made with rice flour from the winter harvest find their way into innumerable pithes, both savoury and sweet, like the doodh puli and patishapta, the latter strongly reminiscent of a glorified French crêpe.

Well, that’s the three categories sorted, something which might be helpful for the present-day sweet-lover. However, it is also worthwhile to take a chronological approach to Bengali sweets to assess their evolution over time. Before the Portuguese, sweets in Bengal were clubbed under the term monda-mithai, a term in popular use even today. Monda were khowa or milk based, while mithai were flour or lentil based. Narus and mowas were prevalent, as were extremely simple sugar-based confectionaries like the disc-like batasha, marble-like nakuldana and the colourful and elaborately shaped mathh. Sar-based sarbhajas and sarpuriyas, pastry-based khajas and gojas, rice-based payesh and pithe: all of these were already present at the scene.

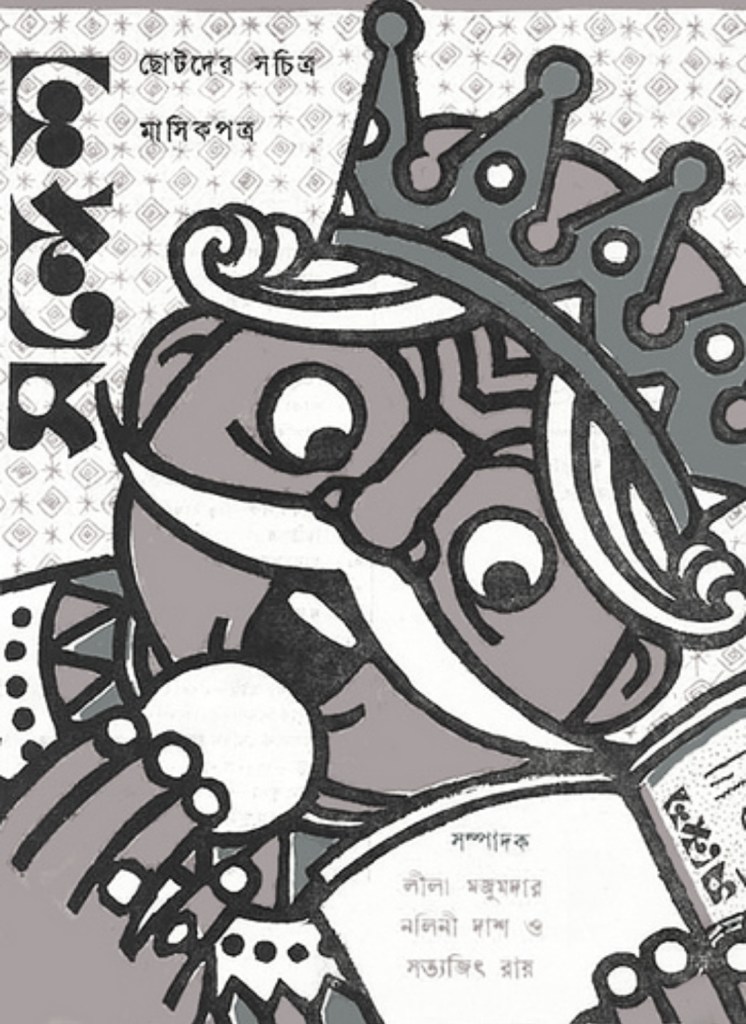

The advent of the Portuguese around the turn of the 16th century was a turning point in the history of mishti, for they introduced cheesemaking in India. They made a kind of cheese by curdling cow’s milk with lime juice or vinegar and draining out the whey. This was kneaded, salted and often smoked. Bandel cheese is still an iconic part of Calcutta cuisine and features in dishes across the city. And it is from Bandel Cheese that the moiras started making chhana and chhana-based sweets, starting with the sandesh. It got its name from Guptipara in Hooghly, a name which also means “news”, a pun put to popular use by the Ray family in their famous children’s magazine centuries later. It became common practice to offer sandesh when delivering good news, which is probably where it got its name.

Sandesh started its life as a shapeless blob, like the modern-day makha sandesh. It was in that the blob evolved into the gupho sandesh, balls of chhana sweetened with sugar. In the 19th century, people started cooking chhana to make the end-product firmer, producing the array of sandesh with varying degrees of paak. Flavours started entering the mix. The list of sandesh varieties started growing. Jatindramohan Dutta’s long list of sandesh includes Monohara from Janai (with a brittle sugar or jaggery crust contrasting the soft sandesh within), Gunfo Sandesh from Panihati, and Ramchaki sandesh from Sodepur, and a myriad of poetic names like Abar Khabo, Manoranjan and Kosturi alongside curiously descriptive ones like chop sandesh, biscuit sandesh and icecream sandesh.

Later in the 19th century, chhana morphed into two other distinct categories of sweets, the rosher mishti (syrup-based sweets) like rosogolla and chamcham and the bhaja mishti (fried sweets) like pantua and lyangcha. The sweet spectrum started broadening, with iconic sweetshops opening up in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Creativity surged, resulting in the formation of interesting concoctions like Bhim Nag’s ledikeni, Nakur’s norompaak jalbhara (soft chhana encasing a liquid center), N.C. Das’s abar khabo (chhana and khoya sandesh flavoured with rosewater and cardamom), Balaram Mallick’s baked rosogolla (rosogolla topped with rabdi and baked till caramelized)……the list goes on.

From soft sandesh to syrupy rosogolla, Shatkigarer lyangcha to Joynogorer mowa, chilled nolen gurer payesh to warm malpua, the world of Bengali sweets is immense and awe-inspiring. We’ve merely scratched the surface here, and here is a lot, lot more to this incredible realm of sweetmaking which is no less than an artform.

Subho Bijoya to all readers of The Gourmet Glutton!