Historical Lingusitics and Etymology

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. I’ve been dabbling with some of its basic concepts for the past couple of months and found certain aspects of it making perfect sense in a culinary context. This month, I’ll try my best to project my rudimentary knowledge of certain aspects of linguistics into the food context in a sort of Multi-Disciplinary Team approach, focusing in particular on three aspects of food words: origin, sound, and meaning. This week, we will deal with etymology, with a side of historical linguistics, in an attempt to see how languages in general and food words in particular, originate, evolve and mingle to create a complex lexicon.

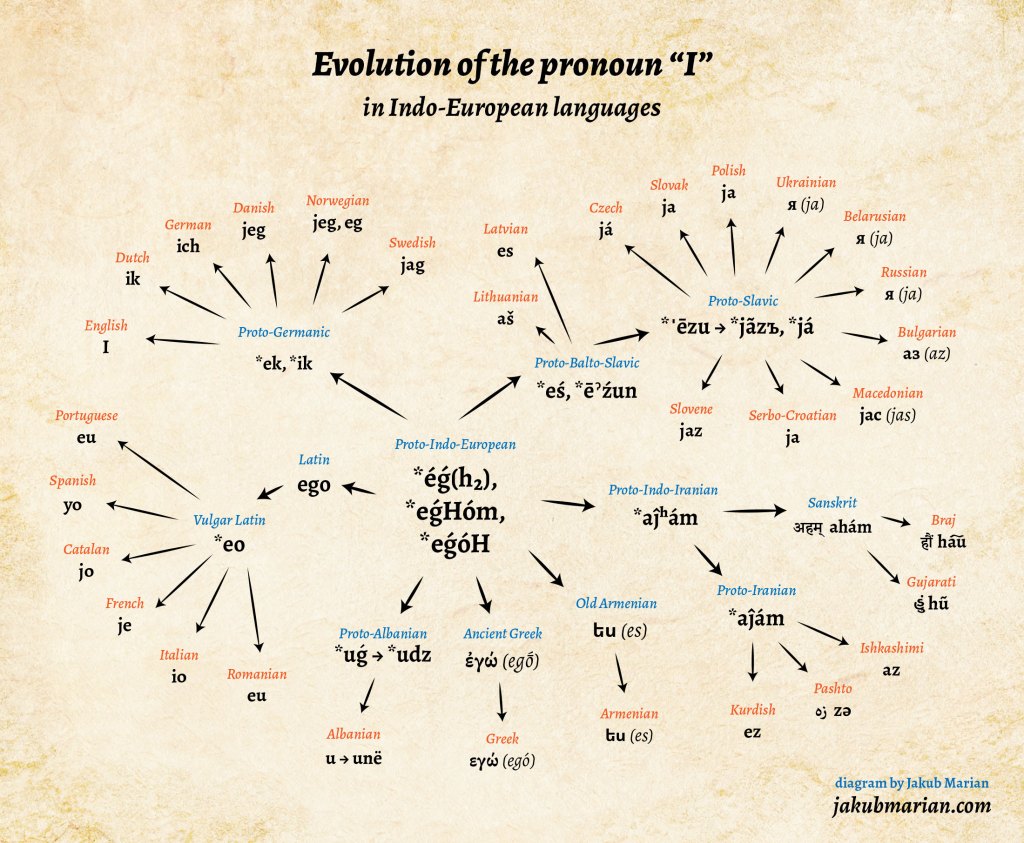

Like species, most languages originate from older languages, and their vocabulary is based on both the parent language as well as the multiple languages it encounters during its evolution. Cognates refer to words in related languages, originating from a common source, which undergo changes over time based on the quirks of the individual languages. For example, the English “milk”, German “milch”, and the Dutch “melk”, all originate from a common Proto-Germanic ancestor. Similarly, the Spanish “leche”, Italian “latte”, and French “lait”, all originate from a common Latin ancestor. Cognates help linguists identify which languages are more closely related to each other, and even trace family trees of languages, one of the most popular being the Proto-Indo-European family tree, which is believed to have spawned a huge number of languages in Eurasia.

But etymology can throw you a curveball once in a while. Take the Italian “pesto” and English “paste”, for example. If you think about it, a classic Pesto Genovese is a mixture of herbs, garlic, pine nuts, olive oil and parmesan, pounded in a mortar and pestle to form a……paste. But the two words are unrelated. “Pesto” comes from “pestare” meaning “to pound or crush”, being more related to the pestle than to paste, while “paste” comes from Late Latin “pasta”, meaning “barley porridge”, which ultimately morphed into “pasta” in Modern Italian. “Pesto” and “paste” therefore have a chance association, similar to the convergent evolution of sharks, dolphins and ancient mosasaurs, all sailing the high seas with their remarkably similar streamlined bodies while being constitutionally distinct from each other. Etymology is murky territory, and it is wise to dig deeper before jumping at conclusions based on superficial resemblances.

/__opt__aboutcom__coeus__resources__content_migration__serious_eats__seriouseats.com__2018__08__20180731-pesto-reshoot-vicky-wasik-10--6b70d2d122ac48df874c280077d433b9.jpg)

With borrowed or loan words, the analogy with evolutionary biology falls short. Unlike cognates, loan words do not undergo gradual morphing over time. Rather, it refers to a word adopted from a foreign language with little or no modification, although the word does undergo some modifications in the new language. Loan words have existed ever since different countries started communicating and trading with each other. English took entrepreneur from French, algebra from Arabic, kindergarten from German, and karaoke from Japanese. It works both ways: Germans took download from English, Japanese took pan from French, and so on. As a foodie in the global age, this category of words has become extremely relevant. We encounter a very high proportion of loanwords on a restaurant menu. Cuisines are starting to blend at an incredible rate these days, bringing a lot of foreign words like sushi, risotto and vindaloo into standard English usage.

The words in a language are steeped with historical significance. Both cognates and loan words provide a glimpse into the past, to the lives of the people peaking it, invasions, and more. One of my favourite examples has to do with meat terminology: English has separate words for the animal and the meat that comes from it: cow/beef, pig/pork, lamb/mutton, deer/venison, calf/veal and so on. In each pair, the first word comes from a proto-Germanic root, many having almost identical cognates in other Germanic languages: “kuh” and “lamm” are German, and “koe”, and “lam” are Dutch for cow and lamb respectively. The words for meat on the other hand, are borrowed from Old French words like beouf, porc, mouton, veau, into Middle English during the Norman conquest of 1066, which is why English is teeming with loanwords from French. It is also reminiscent of the class divide: “English is the language of the cold, filthy field; French is the language of the warm, inviting table”, as Adam Ragusea eloquently puts it.

Let’s illustrate the quirks of etymology with an example. The word “potato” comes from “batata”, the Caribbean word for not potato (Solanum tuberosum), but sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), an entirely different species. The overlap of names was due to a centuries-old mix-up. When Columbus first landed on American shores in 1492, he discovered the batatas and brought them back home. In the 1530s, Spaniards stumbled upon a similar but white-fleshed tuber in Peru, which the Incas called “papa”. Without the foliage, this new white tuber looked a lot like the batatas to Europeans and so they were given the same name. Over time, “batatas” changed to the Spanish “patatas” and finally the English “potato”. When it was later found out that the two species were different, people started calling the orange tuber “common potato” and the white tuber as “Virginia potato”, the term used to denote anything from the New World back in the day, not necessarily just modern-day Virginia. As the white tuber overtook the orange over the next couple of centuries, the “Virginia” prefix was dropped, and people ended up with the same word for two very different vegetables. Since the orange batatas was distinctively sweeter than white one, people started calling it “sweet potato”.

The same transformation occurred in other languages too, like German (kartoffel and süßkartoffel), Dutch (aardappel and zoete ardappel) and French (patate and patate douce), firmly establishing the regular-sweet divide. Interestingly, another French name for potato is “pomme de terre” or “apple of the Earth”, which parallels the Dutch “aardappel” or “Earth apple”. By the way, the German “kartoffel”, actually originates from the Italian “tartufo” or truffles, since both are dug up from the ground. Italians call them “patata” like the Spaniards, although Latin Americans continue to call it “papa”. while the sweet potato is still called “batata” in Spain and Argentina. The word “batata” however, refers to potato in Portuguese, which explains why so many languages on the West coast of India use this term, from the Gujarati batata nu shak to the Marathi batata kachrya. On the East coast however, it is called “aloo”, a word also used in North Indian languages, so we’ve got the Hindi aloo ki sabzi and the Bengali aloor torkari. To throw another spanner in the works, the word originates from the Sanskrit “alu” meaning yam. So now we’ve got three tubers tangled together, thanks to the sticky web of etymology.

What counts as a separate word in the lexicon also varies from language to language. It is interesting to note how different cultures have words in their lexicon that directly correspond to their needs. Even in the pure food realm, certain words highlight culinary practices that are important in certain languages: the Italians have a specific word for the vigorous stirring needed to emulsify fats (like cheese or oil) and starchy pasta water into a creamy sauce: “mantecare”, a word whose roots come from the Spanish for butter (manteca). The similar sounding French term “monter au beurre”, often diminuted to just “monte”, refers to the process of finishing a sauce with butter, a crucial final step in a lot of French sauces like beurre blanc and Bordelaise. While the two may seem like cognates, they aren’t: “monter au beurre” translates to “mount with butter”, so “monte” and “mantecare” come from different sources. Convergent evolution at work, yet again.

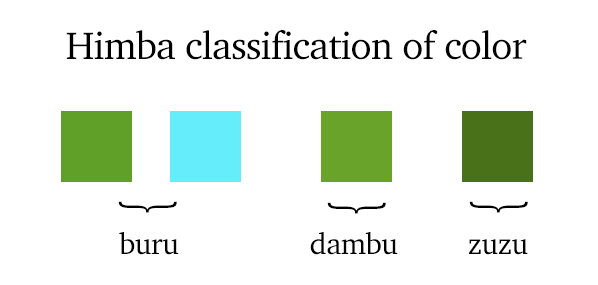

These are the so-called untranslatable words, which tend to be culture-specific. The Bengali “adda” refers to the practice of sitting down and discussing anything from sports to politics to music, accompanied by cups of tea. The Spanish “sobremesa” refers to the practice of lingering at the dinner table and continuing the conversation long after the meal is finished. These are culturally specific words that are difficult to translate, atleast in a few words. Interestingly, the converse is true as well: the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis suggests that the words in a language shapes the thought process of individuals speaking it. A classic example is how the Otjihimba language, spoken by the Himba tribe of Namibia, allocates separate words to light and dark green but not to blue and green, which is why speakers of that language can distinguish between the former pair but lot the latter. This puts thought and language in a chicken and egg situation, making us wonder which one comes first and shapes the other.

The lexicon of a langauge is incredibly dynamic. Remember how we once used the term “groundnut” for the ingredient we use in our favourite nut spread and Thai satay sauce? Words fall out of fashion, only to be replaced by others. Yet others are imported from foreign languages, and some even conjured out of thin air. These are the neologisms, or the words freshly made from scratch, most of which are in the tech realm, like selfies and download. A neologism in the food realm is “Cheetle”, a word that refers to the orange, cheesy dust that sticks to your fingers when eating Cheetos. There are companies in India now selling raw cookie dough and the bottom part of an ice-cream cone that is normally filled with chocolate. These don’t have a separate name as of now, but who knows, they might undergo a naming ceremony when they catch on.

Language is indeed a mirror of history, and our complex lexicon is witness to the complex history of our langauge, as words morphed, old words were dropped, and new words made their way in, from other langauges and sometiems from scratch. Every word has a story to tell, only if you look closer. Next week, we will tackle yet another aspect of linguistics, which is becoming more and more relevant in today’s era of globalization.

One Comment Add yours