Phonetics and Phonology

Last time, we talked a little bit about etymology and word origins. This time, we’ll discuss the sound of words, which is the subject matter of phonetics and phonology. Phonetics refers to the study of sounds in language as a whole, while phonology refers to the specific sounds in a particular language. While the former merely tells us about the physical mechanism of how a sound is produced, the latter tells us about the role that sound plays in a language to convey meaning. With an excessive number of loan words entering the English lexicon, matters of pronunciation have started to arise at a greater rate than ever before.

Let’s begin with sound production, the subject matter of articulatory phonetics. Sounds produced without any restriction in the vocal passage are vowels, while those produced with some restriction are consonants. For consonants, there are three main criteria: where the restriction occurs, whether or not the vocal cords are vibrating during this process, and the degree of restriction itself. For vowels, there are three criteria: height (proximity of tongue to hard palate), backness (position of tongue in mouth) and roundedness of lips.

Different combinations produce different vowel and consonant sounds, for example, “b” is a voiced consonant produced by sudden expulsion of air through the lips, a “voiced, bilabial plosive”, and an “u” is described as a “rounded, high, back vowel”, describing the position of the tongue in two axes as well as the position of the lips. Phonetics is murky territory, and I’m hesitant to delve into details to avoid complicating things any further.

What is more important is the fact that different languages have different sets of sounds, which takes us from phonetics to phonology. Take for example the “r” sounds in English, French and Spanish. The French guttural “r” in “crème brulée”, involves the soft palate and uvula (voiced uvular fricative), while the Spanish trilled “r” in “crema Catalana” involves the hard palate (voiced alveolar trill), while the standard American English “r” in “cream cheese” falls slightly behind (voiced postalveolar approximant). Oh, Spanish has yet another “r” sound, the tapped “r”, which I’m not getting into here.

As croissants and burritos reached America, both French and Spanish “r”s started shifting to the English form, without changing the meanings of the original words. Some sound shifts aren’t so subtle. Then again, subtlety is a subjective term. Bengalis have quite some trouble distinguishing between the “r” sounds in परायी and पढ़ाई, a sound change any Hindi-speaker can easily pick up on. This change is more crucial, since the meaning of the word changes completely, from “foreign” to “study”. What sounds we can distinguish has to do a lot with the sounds we’ve heard growing up.

A great example of this can be illustrated through the name of the now world-famous Korean rice dish, bibimbap. Written down in Hangul script, it looks like 비빔밥. As you can see, the symbol “ㅂ” appears four times in the word. This consonant is called “bieup”, and its sound is difficult to explain to English speakers. It is close to a “p”, which can sometimes change into a “b” during pronunciation, since Koreans don’t have a separate “b” sound in their language and are usually unable to distinguish between the two. The sound can vary between “b” and “p” depending on its position in the word. At the beginning and end of a word or syllable it has a “p” sound, whereas if it gets jammed between two vowels it morphs into “b”.

Hear a Korean pronounce the dish’s name, and it sounds something like “pibimpap, and when the word gets translated from Korean Hangul script to the Latin script, some of the letters change to p, others to b. In Korean, the “b” and “p” sounds are essentially interchangeable, what phonologists call allophones. This is obviously not the case in English, where “bear” and “pear” mean very different things, making “b” and “p” separate phonemes in English, which Webster defines as “any of the abstract units of the phonetic system of a language that correspond to a set of similar speech sounds which are perceived to be a single distinctive sound in the language”.

Asian languages use different scripts that often don’t translate well when converted to English, producing such sound changes. The typically French vowel sound –eu (similar to a Hindi अ sound) as in “pot au feu” got transferred to the Vietnamese phở, where the French pronunciation was preserved, probably because the long period of French colonization had introduced the never-ending list of French vowels into Vietnamese phonology. When phở reached the English-speaking nations, including India, the spelling was taken literally and people started calling it pho (similar to a Hindi ओ sound). Some restaurants try to preserve the original pronunciation by using clever puns (like Pho-king in Delhi), while others undo the effort (like Friends of Pho in Kolkata).

To make matters worse, a lot of Asian languages like Vietnamese and Mandarin, are tonal. In a tonal language, the meaning of a syllable changes depending on not whether you say it at a high, medium or low pitch, and whether your pitch rises or falls while saying it. And that is why when native Chinese speakers pronounce certain dishes like xiao long bao (Chinese soup dumpling) or char kwey teow (Thai rice noodle stir-fry), the sound sing-songy, since they are trying to adhere to the tonal rules, something non-tonal language speakers who have somewhat adopted these dishes into their cuisine have completely thrown out the window.

Let’s consider some pairs of phonemes that exist in most Indian languages which do not exist in English. The pairs p/ph, t/th, k/kh, technically called non-aspirated and aspirated plosives, are separate phonemes in Urdu, Hindi, Bengali and most other Indian languages (a notable exception being Tamil, whose speakers can lovingly ask their bae ‘काना का लिया?”), but are allophones in English. So in Urdu, kitaab (کتاب) means book, while khitaab (عنوان) means title. English on the other hand, tends to use the aspirated “ph”, “kh”, “th” sounds even for words like pizza and tikka (टिक्का to ठीकखा) very different from the original, since Hindi assigns different meanings to “t” and “th”, while Italians don’t have the aspirated “t” sound altogether.

And then there are the two “t”s. Bengali, Hindi, Kannada and most other Indian languages use both hard and soft “t”s, technically called unvoiced palatal and labiodental plosives respectively. Exchanging one for the other completely changes the meaning, so in Bengali taak (টাক) with a hard “t” means bald patch, while taak (তাক) with a soft “t” means shelf. So these two versions of “t” are considered different phonemes in Bengali. But that is not the case with a lot of European languages. English has only the hard version, Romance languages like Italian and Spanish have just the soft one. So words like tortilla and tiramisu end up undergo a change in pronunciation without any change in meaning as they get incorporated into English.

Word exchanges over the centuries have let to phonetic alterations from the original to the native language, sometimes to the point of unintelligilibity. How long ago these borrowings happened is usually evident from how phonetically integrated the words are into the borrowing language. Beef (boeuf) and pork (porc) from Old French are good examples. Another example is the word “avocado”, derived from the Nauhatl language of the Aztecs, from the word “ahuacatl” (which also translates to “testicle”, btw), from the tome when Euroeapns reached America, or “curry”, from the Tamil “kari”, back when the Europeans reached India. The word has changed considerably over the past centuries into a pretty Anglicized word. Korean bibimbap and Indian pani puri on the other hand, are relatively new imports into the English-speaking word, which is why they haven’t yet integrated in as seamlessly.

Given enough time, and depending on the language, the word change can be pretty radical. French has a tendency to have a lot of unpronounced letters in its words, like bouillabaisse and ratatouille. On the other hand, Japanese phonology is very different, with the norm of following every single consonant with a vowel, as in butakakuni (pork belly) and okonomiyaki (a type of pancake). When English words get borrowed into Japanese, an extraneous number of vowels get added in as the Latin script gets translated into the Katakana script (a detailed discourse on Hiragana and Katakana is well beyond my knowledge), which almost always have a consonant followed by a vowel, turning the French croquette into korokke (コロッケ) and the disyllabic English ice-cream into the pentasyllabic aisukuriimu (アイスクリーム).

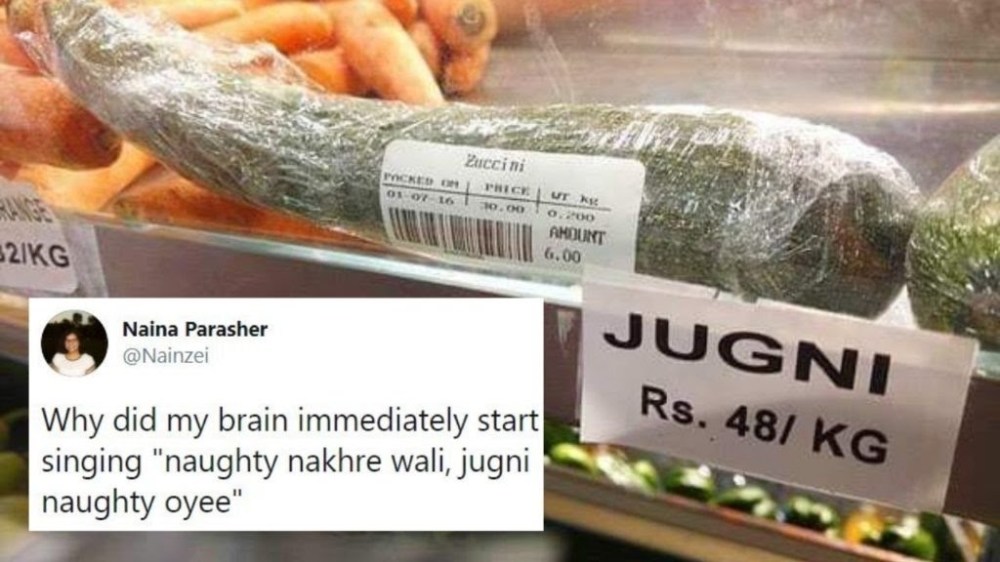

I remember watching a comedy sketch years ago where a guy in a restaurant specifically overpronounces foreign words like bruschetta and croissant, much to the dismay and annoyance of his friends. It was funny, and deals with a linguistic conundrum that is becoming more and more relevant as the years roll on. What is the correct pronunciation of burrito? Do you roll the r, articulate the t? In an era where Americans have started pronouncing the silent “t” at the end of French loanwords like croissant, unsuspecting Bengalis end up pronouncing the silent double “l” in paella, and Punjabis have proudly started selling “jugnis” in their supermarkers, an attempt to appear super-authentic can come off as weird and annoying.

The “it’s not parmesan, its PARMIGIAAAANOOOOO” argument doesn’t really in the present day, in my opinion. Pronouncing a croissant with a guttural r and a silent t might be a bit much if you’re trying to buy a Bauli from the grocery shop near your house. But if you’re in a Parisian boulangerie, or talking to a French person, you could unleash the Frenchman inside you. It’s all about context. In fact, chances are that the authentic French pronunciation might throw off Pintuda, and you will not get your Bauli. So, don’t be a douche, ask for a “krosent”, and save your uvular fricatives for when you visit Paris.

Next time, we will conclude our trilogy with an exploration of yet another aspect of linguistics. Enough of history and sounds, it’s now time to dig into the meaning of it all.