Semantics and Pragmatics

So far in our series, we have examined etymology and phonetics, with interesting culinary digressions. This week, we will focus on two branches of linguistics that deal with meaning of words in a language. While semantics deals with the literal meaning of a word in a sentence, its counterpart, pragmatics, has an emphasis on context, or the intended meaning of the speaker. While we will take a customary glance at pragmatics towards the end of the article, most of our discussion will be centered around semantics.

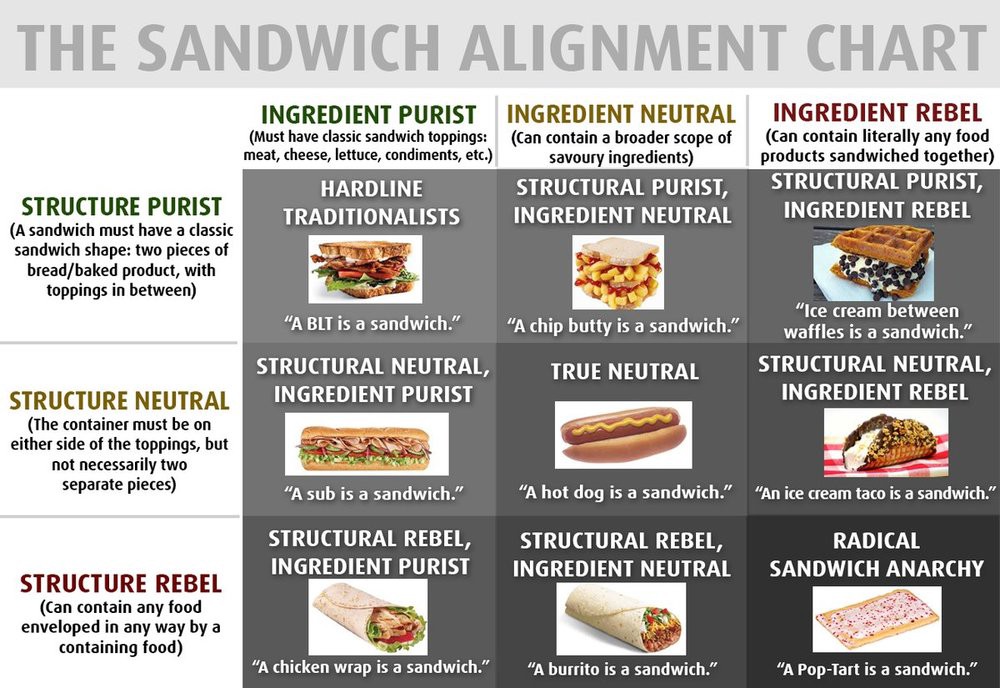

In linguistics, words act as signifiers while the idea or object is the signified. The word “cake” for example refers to the fluffy baked good made with flour, eggs, butter and sugar. The problem arises when signifiers and signified don’t have a one-on-one relation. When I say “sandwich”, you are probably thinking of two slices of white bread with some sort of filling, be it peanut butter and jelly, or simply some sliced up tomato, onion and cucumber. But hot dogs, burgers and shawarmas also fall into the OED definition of sandwich: “two slices of bread, often spread with butter, with a layer of meat, cheese, etc. between them.” The definition of “sandwich” is in fact, quite open, yet we usually don’t think of a Big Mac or a burrito as a sandwich. How far are you willing to loosen the definition?

This “alignment chart” concept can gets dragged to absurd proprortions, leading to such absurd conclusions such as “Saturn is a tea”, or the ridiculous debate “is cereal a soup or is it a salad?” The thing is, if we stick rigidly to definitions, some of these assumptions can make sense from a logical standpoint. But that isn’t how semantics work. Our brains tend to latch on to a prototype “signified” for every “signifier”. When I say “chips”, Indians and Americans would think of Lays and Pringles, while Brits would think of crispy potato batons served with battered cod or halibut. “Entrée” refers to the appetizer course in Europe and Australia, while it refers to the main course in America. For Bengalis, “chop” and “cutlet” are fried snacks, while in the West they refer to cuts of meat. Gravy means very different things in Lucknow, London, and Louisiana. The list goes on. Words change with context, often dramatically, so a certain word “signifier” doesn’t always have the same meaning across all cultures.

Semantic quirks shed some interesting light on food habits of different cultures across India. In Bengal for example, the word “bhaat”, literally “cooked rice”, is often used as a synonym for food. “Bhaat kheye jaben” implies “do have lunch/dinner before you leave”, the rice being used as a marker for the whole meal, indicating its significance in the Bengali diet. A similar phenomenon is seen in Tamil with “sooru”, also meaning rice. Haryanvis on the other hand, would say “roti khaake jaana” to mean the same thing, the role of “bhaat” being taken over here by the “roti”, which is a lot more dominant in the wheat belt of North India. Hindi does not have separate words for uncooked and cooked rice, both being referred to as “chawal”. Rice-eating cultures like Bengal and Orissa of course, designate them separately, as chaal and bhaat (anna in formal or sadhu bhasha) in Bengali, for example.

The Dravidian languages take this an interesting step further. Unlike Bengal, where plain cooked rice is usually eaten with daal and other sides, the Southern states often use the rice to create more complex dishes. In Kannada, uncooked and cooked rice are called “akki” and “anna” respectively, the latter indicative of the strong Sanskrit influence on the language. And then there is “bath” , a word reserved for the myriad of dishes they make with the plain rice, be it the spicy vaangi bath with brinjals, or the extremely popular bisi bele bath, which literally translates to “hot lentils and rice”, their version of the khichdi. The same thing is seen in other Dravidian languages like Tamil and Malayalam, with separate words for uncooked rice, cooked rice, and spiced rice dishes. From Chandigarh to Chennai, the rice vocabulary gradually increases.

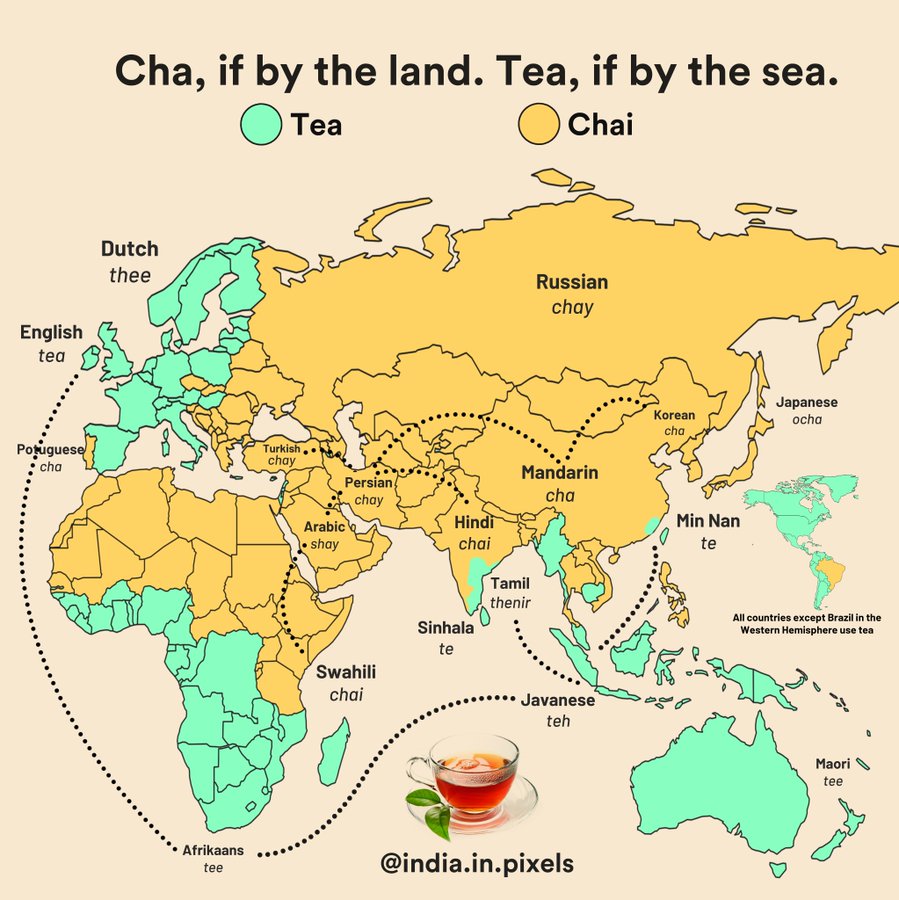

Let’s move on to another example. You can determine the route through which China connected to a specific part of the ancient world, just from the name they use to refer to tea: “Chai, if by land. Tea, if by sea”. This is because seafarers were exposed to the the Min Nan word “the” from the coastal province of Fujian, while the Mandarin “cha” travelled through land, via the Silk Route. A notable exception is Poland, where it is called herbata, derived from a brand of tea that was introduced in Poland by the Dutch. It was called herba thee (literally herb tea), from which the Polish dropped off the “thee” and modified the first name into “herbata”. From Poland, this word migrated into neighbouring countries Belarus and Lithuana, where it is called “harbata” and “arbata”, respectively. If you think genericizing a brand name and dropping off crucial roots like “thee” is weird, let me take a quick detour to give you two examples closer to home.

The word “chowmein” derives from the Chinese “chǎo” meaning stir-fried and “miàn” meaning noodles. When this word entered the Calcutta lexicon via the Hakka Chinese community, we conveniently dropped off the crucial root for noodles, abbreviating it to just “chow”. As a result, “chicken chow” essentially translates to “chicken fry”, but nobody in Kolkata would think that. “Chow” actually means “eat” in an American context; and if you say “chow” to a Kannadiga, they will immediately start thinking of “chow chow bath”, a dual dish of savoury (khara bath) and sweet (kesari bath) semolina. As for the brand name bit, I remember vividly how Cadbury and chocolate were interchangeable terms during my childhood, a fact that changed later with the advent of other brands like Amul, Hershey and Toblerone into the Indian market, once wholly dominated by Cadbury. Both “chow” and “Cadbury” prove that events like these happen all around the world, the “Herba Thee phenomenon” being a case in point.

Like the Polish, the British too were first exposed to this beverage via the Dutch navy in the 1650s. Its popularity soon spread throughout the nation, and tea is now, without a doubt, a big part of British culture. Tea started gaining popularity in India in the turn of the last century as a result of the British, and soon Indians started adding their own blend of spices to enhance the flavour of the tea. The Brits loved our style of spiced tea, which they started referring to as “chai tea”. While the term is definitely a tautonym, it is noteworthy that while “chai” and “tea” are synonymous in India, in the West “chai” is a subset of tea, what linguists would call a hyponym. Even if the Brits contract “chai tea” to just “chai”, they will not be using the word to refer to their cups of Earl Grey and English Breakfast, unlike us who would use the term even if we end up using an Earl Grey teabag and no elaichi to brew our cuppa. Although it would be more accurate to call it “masala chai” there is also no denying that “chai tea” is a term laden with historical and etymological significance, combining two different roots of the same word.

That being said, it still sounds super pretentious when used by an Indian, justifying my unshakeable resolve throw a shoe at any South Delhi douche ordering “tea tea” at Connaught Place. The meaning of a word depends greatly on the cultural context, which is why a coconutty Indian describing a pina colada as a “tropical” drink sounds downright weird. This is the realm of pragmatics, the study of language in context. You’d be weirded out if you saw a packet of “asbestos-free flour” at the supermarket. If you ask the about the pork chop and he recommends you try the steak frites, he is implying that the pork isn’t that good. If they waiter then asks you about the the steak frites tastes and you say “the potatoes are really good”, it indirectly implies that the steak isn’t up to par. Each example implies something more than what is directly stated. Daily communication is based on Grice’s Maxims, a set of four assumptions that whatever is being said is meant to convey some information or the other, and flouting these maxims creates interesting scenarios. A detailed discourse of Grice’s Maxims is well beyond the scope of this series.

And finally, we cannot talk about pragmatics without a brief mention of phatics, fancy jargon for “small talk”. These are phrases used more as a means of establishing communication rather than to impart information. A waiter asking you “what would you like to start off with” requires information on the your part; he is waiting for some sort of input: tandoori chicken or drums of heaven? On the other hand, if he comes over at the end of the meal and say “It was a pleasure serving you, do visit again, goodnight”, it is mere social courtesy. He isn’t expecting you to rant off about how you wouldn’t be able to visit for the next year since you’ll be out of town, or that your night is actually going to be terrible since you’re on your way to the ER for a night shift until the next morning, that too on Holi, in Haryana. All you need to do is smile, nod approvingly, and leave (after paying, of course).

That concludes our crash course on linguistics from a culinary context. Understanding the words, their origins and pronunciation, and their meanings across cultures sheds a great deal of light on culinary history as well, re-establishing our unity in diversity.

One Comment Add yours