Recipes are everywhere these days: from cookbooks to websites, from television to magazines. A recipe contains instructions to make a dish, but how detailed must those instructions be? Which recipe is better, the one that goes into excruciating detail or the one that is more open to interpretation? Can you cook without a recipe? To answer these questions, allow the nerd in me, who loves putting stuff along a scale and into tables, to introduce the Exactitude Scale. It describes how detailed a recipe is, and there is quite a lot of variation in this respect.

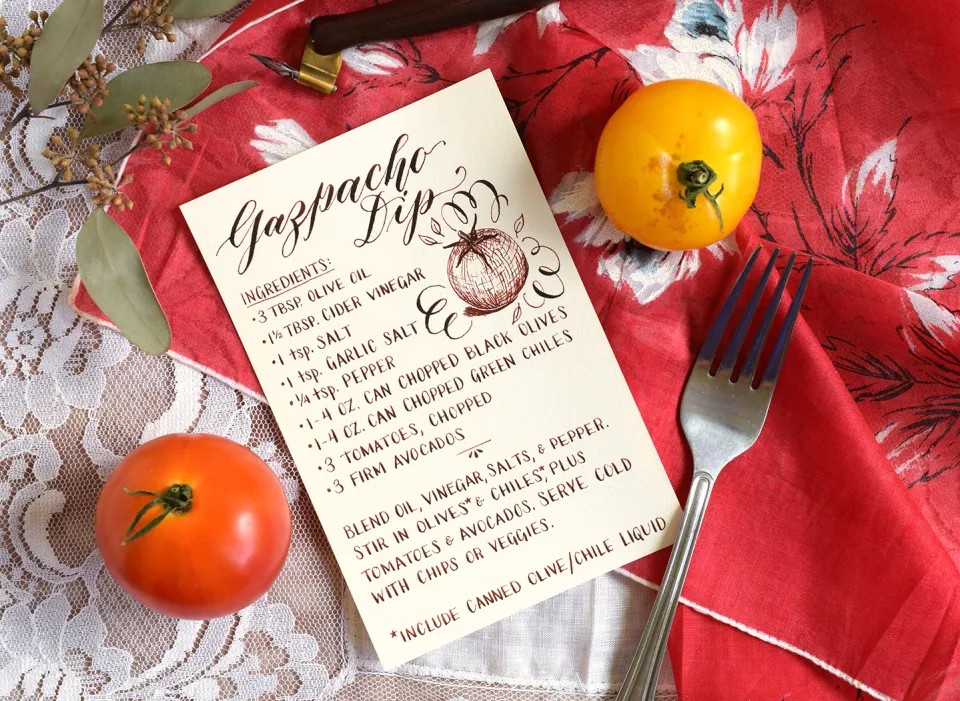

In the middle of the scale lie the normal recipes: you know, tablespoon of oil, salt to taste, 2 cups flour……the usual stuff. Why are these the norm? The obvious reason is that it lies in the Goldilocks sweet spot: you have enough detail but not too much. You’ve got the ingredients list to begin with, and a simple description of how to make the dish. Cups and tablespoons are easier to measure with, and is much easier to get your head around than grams. In short, it is convenient.

On the vague end of the spectrum lie a couple of classic French cookbooks. Le Guide Culinaire by Auguste Escoffier, first published in 1903 is a classic which is still in print. Another similar book is the 1914 Le Repertoire de la Cuisine. Both books are chock-full of recipes, if you could them recipes that is, because these are unlike any standard recipe you’d find these days.

Here is the recipe for the classic Crème au caramel from Le Guide Culinaire: “Clothe the bottom and sides of a mould with sugar cooked to the golden caramel stage, and fill it up with vanilla flavoured, moulded custard preparation. Poach it and turn it out as desired.” This is nothing more than plain, direct instruction with no reference to quantities. The recipe for the vanilla custard using quarts and cups is mentioned separately in the book, which you need to look up.

There are sections devoted to technique, before jumping straight into an array of three-line recipes, around three thousand of them. Sauce recipes build on simpler sauces that build on stock recipes, and so on. The tone of the book is that of a busy head chef briefly communicating the idea of the dish to an experienced line cook. It utterly confusing for the starry-eyed novice home cook, just as much as a Nick DiGiovanni TikTok (I’ll get to this abomination in a future article) or a Tasty recipe video, albeit in a different way.

On the other extreme of the scale is the overly specific content, and the best example for me is Bong Eats, who go into unbelievable detail when it comes to recipes. Their recipe for a simple mishtir dokaner aloor torakari for example, measures the exact number of grams of each spice. I had made their katla kalia once which called for 20 grams of ginger, 30 grams of tomato, 4 grams of cumin, 27 grams of sugar, 35 grams of salt……you get the gist.

Why measure out grams of ginger when you can just break off a thumb sized piece? Not everyone has access to fine weighing scales, so teaspoons and tablespoon-based recipes are much easier to follow. Recipes like these are not meant for the casual weeknight meal, and require more investment. So, what is the upside to all this inconvenience?

Firstly, precise recipes like these are ideal when trying to scale up: making a dish for 10 or 20 is much easier to do when thinking in terms of grams, since it is very easy to lose track of scale in such quantities, like estimating the amount of salt, especially you’re a novice. The main purpose of these scientifically precise recipes however, is to provide the foundation, like the Broadway standard that gets swung into a jazz masterpiece.

Say you’re an adventurous Italian who wants to try out a katla kalia. He has never had it before, and has no idea what the final dish should taste like. He is unsure of the quantities. The whole array of spices confuses him. He isn’t aware that the tomatoes in the dish aren’t meant to be as zingy and bright as in a cioppino (the classic fisherman’s stew from Italy) or that you need to add a lot of sugar to make sure the final product has a sweetish taste. There is no instinct at play here, no square one.

This is precisely where following a recipe to the T helps. It helps you perfectly replicate an unknown dish. Cups and teaspoons are convenient, but aren’t standard by any stretch of the imagination. In unfamiliar territory, this is a recipe for failure. This approach is also very crucial in baking and confectionery, where minute changes can drastically affect the final product.

With experience though, things begin to change. I’ve made enough cakes to understand how the batter should feel without relying too heavily on my scales. One you are certain how the final dish should taste, it is easier to make adjustments. Another sprinkling of salt, the final squeeze of lime, two more minutes of cooking: you know the exact shortcoming of a near-perfect dish, and nudge it towards that perfection.

Samin Nosrat devotes half of her book Salt Fat Acid Heat to basic cooking principles before going into recipes. Uncle Roger playfully cirticised Joshua Weissman to ditch his grams and mililiters and start throwing stuff into the put. Developing this sense is the most important virtue of a chef. The rigid recipe is a starting point, not the end goal. Once you’ve made it in the standard way, it’s time to start tweaking. Without tweaks, there would have been no aloo in biryani, no masala chai panna cotta, and no cronut.

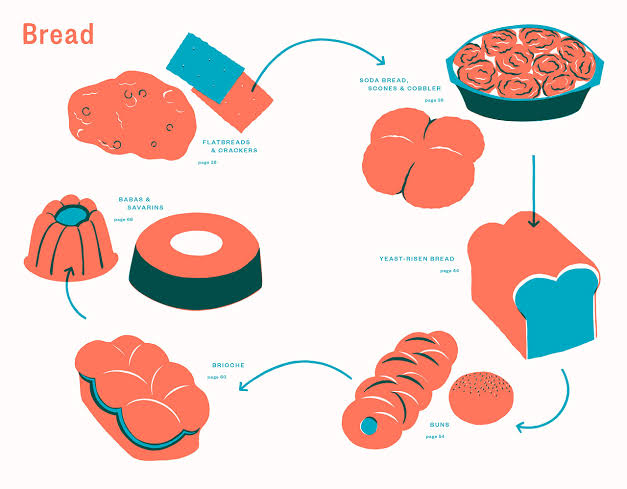

Lateral cooking by Niki Segnit is a recipe book like no other. It puts recipes along a spectrum; the bread spectrum for example starts with the basic flatbread, then moves on to leavened breads, leading up to the desserty concoctions like babas and savarins. The road is long and slow but meticulous, and shows how tweaking one recipe leads to the other. There are recipes, but the overwhelming focus is on variations and derivatives, showing how one basic recipe spawns ten more. Cooking becomes freer, unshackled, just as it should be.

Once you reach that stage, the French cookbooks we talked about at the beginning start making sense. With your foundation in place, you start to improvise. Learn how to braise an ox tongue or cook rice perfectly, and use that to create numerous variations. Books like these are liberating, freeing up more space in your bookshelf and your head. Less attention to tiny details opens up more pages for improvisation, which is why this book can fit 3000 recipes into 800 pages and still make room for the basics.

Recipes are like training wheels: you definitely need them at the start or you will stumble and fall, but unless you let them go at the right time, they will pull you back and hinder your progress. So go ahead, get the basics straight, then take off the recipe training wheels and pedal head. The road is long and exciting, and it’s a journey worth taking.