The Potato Chronicles: Part 2

Last time, we explored the history of the potato upto the mid-18th century, interspersed with a few simple dishes that use the potato skin and boiled potatoes. There are two things you can do with boiled, peeled potatoes: you could cut them up into little pieces, or pulverise it into mash, the earliest recipe of which comes from the same time, from the Art of Cookery by Hannah Glasse, published in 1747.

The Western ideal of the mash is a smooth, velvety concoction, ensured by passing the boiled potatoes through a ricer followed by an additional step of sieving it to remove any lumps. It can then be seasoned, enriched with dairy like milk or butter, and amped up with flavours like garlic and herbs. This simple blueprint for a mash is a mere starting point for a wonderful array of textures and flavours. For the textural side of the spectrum, we need to examine two absolute classics from France.

The iconic pommes Aligot, a speciality of Auvergne in Southwest France, combines potatoes and cheese, traditionally tomme fraiche in an almost 2:1 ratio to produce a fondue-like dish with a texture that is more stringy than creamy. Daniel Gritzer from Serious Eats refers to this ridiculously delicious, calorific concoction as “mountain fare” and “true winter food, best eaten in a snowy landscape”. If you’re not charting mountain terrain and craving something less, well, artery-clogging, Monsieur Robuchon has you covered.

On paper, the iconic mash of chef extraordinaire Joel Robuchon looks rather simple, maybe verging on the underwhelming: potatoes, butter, milk, and salt, c’est tout. What creates the magic is deft technique and a judicious choice of ingredients. For his mash, Robuchon uses French waxy potato called La Ratte with a buttery texture and nutty notes of chestnut. The resultant mash is so unbelievably creamy and decadent and it has become the chef’s signature dish. People have been known to order portions of the mash instead of dessert at his restaurant.

Moving on now from texture to flavour. Much like the eggplant, the potato is a flavour sponge, and a simple mash can effortlessly imbibe local flavours and attain a distinct geographical identity. The Greek skordalia subs out the butter for olive oil and adds in garlic, parsley and spring onion. The Bengali aloo sedhho uses sharp, punchy mustard oil or nutty, caramelised ghee as the fat, along with bits of green chilli or coriander. The Scottish clapshot is a mix of mashed potato and turnip flavoured with butter or dripping, with some chives. The change in the choice of fat creates a drastic difference in the taste of the final mash.

The addition of various inclusions creates a huge variety of mashes all over Europe. The Danish brændende kærlighed, literally “burning love”, comprises mash topped with brown onions and bacon. The Dutch Stampott is a winter classic that can include anything, from sauerkraut to endive, kale to spinach, and is traditionally served with a piece of rookworst sausage. The Irish champ uses green onion and stinging nettle, and then there is the Colcannon, also from Ireland, which uses cabbage or kale, with the occasional addition of ham or bacon.

Potato and Ireland go hand in hand. It was one of the first places to adopt the Devil’s Apple and by the mid 19th century, it became the only source of sustenance. Which is why when the Irish Potato Famine (simply called the Great Famine in Ireland) hit in 1845, it led to catastrophe. The culprit was a fungus, Phytophthora infestans, colloquially referred to as Potato Blight. It reached Europe from the New World through guano, made from bird droppings and used as a fertilizer in Europe to maximise potato cultivation during the Industrial Revolution. Although the blight hit most parts of Europe, Ireland was the most devastated. Almost a million died, which is why Ireland is still the only country till date which has had a dip in population since the 19th century.

However, once the famine subsided, the popularity of the spud grew further and further, until it became almost equivalent to coal; with the former fuelling the Industrial mills and the latter fuelling the stomachs of people running them. As Adam Ragusea mentions: “more potatoes equals more people”. A 2011 paper bu Nunn et al tried to mathematically calculate just how much of a role the potato played in the massive population boom in Eurasia and Africa from the 19th century onwards, amidst other factors like medical and technological advancements, and concluded that almost a quarter of the rise can be attributed to the humble spud.

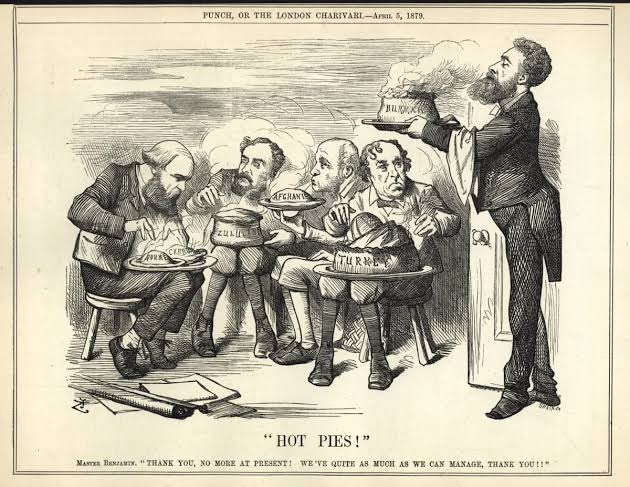

The Industrial Revolution and the population spikes at this time also coincided with that all-important historical phenomenon: global colonization. And as I said, they are all related. It was 19th century Europe’s obsession with the potato that took it to far-flung corners of the world. Much like the Columbian Exchange from a few centuries ago, the era of Global Colonization by Europe opened up new avenues, for better or for worse. Arseny Knaifel aka Andong believes that the Eurocentric world order which develooped in the 19th and dominated a lot of the early 20th century, owes a lot to the potato. Devil’s apple indeed.

Denis Diderot, in his 18th century magnum opus Encyclopédie, called the potato an insipid product that “cannot be regarded as an enjoyable food but proves abundant, reasonably healthy food for men who want nothing but sustenance”. But potatoes, much like its nightshade cousin the eggplant, are the perfect sponge for a veritable smorgasbord of flavours, especially so in the global context. More on that next time.