The Potato Chronicles: Part 4

Last time, we talked about global applications of the mash before taking a long detour into food science and concluding with a trio of Indian breakfast classics that hero the humble mash. A spiced mash also forms the basis for a huge array of deep-fried streetside treats in India. It’s time to hit the road, Jack.

A mash sandwiched between two pieces of bread, dunked in a chickpea batter and fried gives you a bread pakora, common in North India. The South Indian bonda uses our old friend the palya, encased in a chickpea coating and dunked in hot oil. The Bengali aloor chop is similar, although it may have a spoon or two of punchy mustard oil added to the potato mix instead of the curry leaves for a touch of regional flair. But the starchy duo of bread and potatoes goes a lot further on the Indian streets.

One of the most famous of these is the iconic Pav Bhaji from Mumbai, The potato forms a huge part in the delicious concoction, flavoured with an alchemic mix of spices The USP of a good pav bhaji is the almost illegal amounts of butter that goes into it, both into the bhaji itself and used to toast (nay, drench) the pav. Another potato-based beauty from Chowpatty is the batata vada, a bonda-esque concoction made using a chunky mash mixed with onion, cilantro and spices, dunked into a spiced chickpea batter and deep fried.

A batata vada is great on its own, but it gets even better when liberally drizzled with a duo of chutneys that is a staple of the Indian street food repertoire. One of these is the deep-brown concoction of tart tamarind and sweet dates, spiked with the earthiness of jeera (cumin), the heat of saunth (dry ginger) and the cooling effect of saunf (fennel seed). The other is a vibrant green spicy mix of cilantro and mint leaves, spiked with green chilli. Add on a liberal sprinkle of spicy peanut-red chilli chutney, adorned with a piece of fried green chilli, all encased in soft, fluffy bun, et voila! You’ve got yourself the world-famous vada pav.

Go to Gujarat and you are greeted by the same bun and mash combo in the form of a dabeli, where usual spiced mash has been additionally sweetened in a signature Gujju style with a generous drizzle of sweet chutney. Served between two pieces of pav toasted on a tawa with a generous accompaniment of finely chopped raw onions and those ridiculously addictive spiced peanuts the Gujaratis excel at crafting, a good Kutchi Dabeli can give any slider a good run for its money.

Speaking of sliders, one of the most popular vegetarian options in most international burger chains across the nation uses yet another potato-based classic, the famous aloo tikki. A mash flavoured with cumin, coriander, ginger and green chillies is shallow fried on a tawa till it is crispy on the outside and soft within. The stalls have wide tawas that have the tikkis par-cooked and arranged around the rim, waiting for a final fry in oil before landing on the customer’s plate.

While aloo tikki is a delicious snack just as is, it too can be taken further. The cool creaminess of yoghurt mellows out the fattiness of the tikki and reins in the earthiness of cumin and the heat of red chilli. Add to that the welcome accents of our duo of chutneys, the aloo tikki chaat is a lip-smacking delight from the bylanes of Old Delhi that is truly hard to beat. Mumbai’s answer to it is the delightful ragda pattice, which Anglicizes the tikki by name and pairs it with curried yellow peas instead of yoghurt to create a dish that tastes completely different.

Moving on now to what is perhaps one of the most superlative of Indian street foods, every aspect of which is highly controversial and hotly debated. Even the name varies across states. From golgappa in Delhi and Punjab to pani puri in Mumbai, From Phuchka in Bengal and Assam to Gupchup in Madhya Pradesh and Chattisgarh to paani ke batashe in Uttar Pradesh. Some claim that the dish was created by Draupadi when her mother-in-law Kunti asked her to make something with leftover sabzi and dough to feed the five Pandavas. Others trace it back to Mughal times where people started spicing and flavouring insipid boiled water which became necessary to consume during a cholera outbreak (oh the irony!!!)

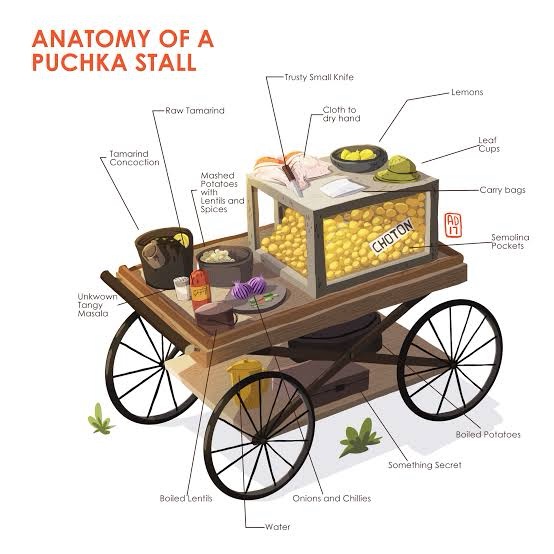

At its most basic, the dish comprises three components: a round piece of pastry that puffs up in the oil to create a hollow shell, which can then be filled up with goodies. The loaded shell is then dunked in a spicy water, and consumed in one go. In the Northern states, the shell of a golgappa can be made of maida (wheat flour) or semolina (sooji), each with a slightly unique texture, with a lot of strong supporters on each side. As for filling, the panipuri from Mumbai employs chickpeas or beansprouts, while both the golgappa and phuchka usually use a spiced potato mash, quite chunky and textured.

While the phuchka usually gets served with a single option of tangy tamarind water, almost everywhere else you will have an option of at least two, one a touch sweet and the other bordering on spicy. The choices of flavoured waters can go berserk, and I have tasted streetside panipuris in Bangalore, six a portion, served with six different flavours ranging from hing (asafoetida) to dahi (yoghurt) to lehsun (garlic), as well as chic version at a Modern Indian place in Delhi, serving up unconventional flavours such as pineapple and pomegranate. No fine dining place however, can match the taste and the theatre of the streetside version.

The guy at the stall deftly serves multiple people at once, going round in circles. He has a rhythm about him, punching a hole in the crisp poori, filling it up with goodies, dunking it in the flavoured water, and placing it on the leaf plate of the eater, who gulps it down in one go, and deftly slurps up the bit of water that trickles onto the plate, and eagerly awaits their turn. You might ask him to adjust the flavors a touch: a touch more black salt, another squeeze of lime, or a bit more spicy. Ask, and ye shall receive. Bhaiya will oblige, and keep you serving until you, filled to the brim with golgappa goodness, raise a trembling hand, begging him to stop. A final sookha (dry) poori : an unpuffed papri topped with the potato mix and seasoned with salt and lime, brings the odyssey to a very happy ending.

These chaat stalls also serve up other stuff, essentially variations on a theme. There is the dahi poori and ragda poori, equivalents of the aloo tikki chaat and ragda pattice respectively. The unpuffed pooris can go into a papdi chaat, or served up sans yoghurt as sev poori, generously covered with a layer of crunchy sev. The phuchkawala from Kolkata has a rather ingenious way of using up unpuffed pooris. By crushing them up and mixing it with cut, boiled potatoes, boiled Bengal gram and yellow peas, and flavouring it with the tamarind water, he concocts the delightfully onomatopoeic churmur, which is a local favourite. Is a churmur a deconstructed phuchka? I’ll let you be the judge of that.

You might disagree with me on the supremacy of the Bengali shingara, the gastronomical categorization of alu kabli, and the origins of the golgappa (or is it pani puri?), but there is no denying the fact that Indian Street Food puts the potato front and center, showcasing it in all its starchy glory. The West is also equally inventive with mash, and goes well beyond a meagre accompaniment to medium-rare steaks and grilled chicken thighs. More on that next time.

yummy !! India is blessed with the type of snacks called “chaat” ..

LikeLike